Sustainability at Trinity: How our Historic College is Reshaping its Future and Leading from the Ground Up

Sustainability at Trinity College is not a gesture of the moment, nor a response to external pressures. It is a fundamental extension of the College’s centuries old charitable objective of “advancing education, learning, religion, and research” ‒ a mission explicitly conceived to endure in perpetuity.

That intention, long established as a marker of institutional stability, now takes on profound new meaning in a world facing complex environmental, social, and economic challenges. “There’s no longer a separate conversation about sustainability,” says Emma Davies, Junior Bursar at Trinity. “It’s in the room with every decision now – from where we allocate capital, to how we build new spaces and how we engage with students.”

Leading positively on the sustainability of the College, estate, endowment and of our activities is now fully reflected in the College’s priorities and embedded in its governance through forums such as the Climate Change Working Group, with a focus on:

• taking a lead role in funding sustainable research;

• providing funding for studentships and prizes to support engagement in sustainability;

• leveraging the College’s convening power to bring policy and research together, sharing lessons learnt;

• understanding and reducing the College’s environmental impact, focusing on food, waste, and energy use;

• using the College’s expertise to reduce reliance on fossil fuels in ways that others can follow;

• investing positively in the College’s operational estate, including by enhancing biodiversity and decarbonising our buildings;

• evolving the endowment to achieve the dual long-run goals of CPI+5% returns while having a positive environmental impact.

The past year has only accelerated the need for attention. Global temperatures in 2024 were the highest ever recorded, and for Cambridge in particular, a city shaped by its historic buildings, green spaces and river, which frequently breaks temperature records, resilience is no longer theoretical. In this feature, we explore how Trinity is translating its enduring mission into contemporary action: rethinking its estate and energy use, reshaping its investment approach, enabling leading-edge sustainability research, and listening to the concerns and creativity of its wider community.

A buff-tailed bumblebee picking up pollen from a crocus on the Trinity Backs. © K Wells.

A buff-tailed bumblebee picking up pollen from a crocus on the Trinity Backs. © K Wells.

A Sustainable Estate

For Trinity, sustainability across its estates and operations begins at home – in the bricks and boilers that enable daily College life. Thoughtfully preserved and updated, many of our buildings have operated for centuries, sustaining generations of students and Fellows. Nonetheless, making a sixteenth-century institution compatible with twenty-first-century climate goals is no small feat. A target is in place to have 90% of all Trinity’s buildings degasified by 2033 with the College adopting a pragmatic but ambitious approach: retrofit where possible, replace where necessary, and reimagine the systems that bind it all together. The programme covers the entire 36- acre site, which currently relies on 21 boiler rooms serving all estate buildings in varying combinations.

The installation of air-source heat pumps is a key component of our pilot decarbonisation initiatives.

The installation of air-source heat pumps is a key component of our pilot decarbonisation initiatives.

In 2023–24, detailed proposals were completed for the first phase of the College’s heat decarbonisation strategy. This includes two of the College’s newer residential sites – Burrell’s Field and Pearce Hostel – which will pilot a shift away from fossil-fuel-based systems toward efficient, electrified heating solutions. To help accelerate this, a Heating Systems Working Group has undertaken an intensive programme of design and cost workshops, and hosted its first Fellows’ Town Hall, which provided an opportunity to share the principles guiding the programme, present key findings from RIBA Stage 2, and outline the issues being carried forward into RIBA Stage 3. Danielle Smith-Turner, the College’s Climate Change Delivery Manager observes: “The decarbonisation of our estate is a significant investment and marks an intentional shift away from fossil-fuel based systems. Pilot decarbonisation initiatives at Burrell’s Field and Pearce Hostel show how institutions can take bold, pragmatic steps toward a sustainable future without significantly impacting the fabric of the existing structure.”

The progress here represents more than just a technical task. It is a rethinking of how comfort, efficiency, and heritage can coexist. The designs incorporate airsource heat pumps, low-temperature heating distribution, and smarter controls, all embedded with a respect for the visual and structural integrity of the buildings. They also provide a foundation for scaling similar interventions to other parts of the estate, including more architecturally sensitive areas.

Over the next five years, the programme aims to continue to deliver phased projects across the estate, carefully balancing the ambitious decarbonisation target with other critical College priorities, including the refurbishment programme and the Trinity 2046 masterplan.

In addition, the College continues to engage with the Cambridge City District Heat Network, which is developing a business proposal for a city-wide district heating system. This ambitious initiative has the potential to deliver significant long-term benefits for the College, the University, and the wider city. Trinity is actively involved in understanding how this project might align with its own sustainability ambitions and in supporting wider initiatives that facilitate decarbonisation across the city.

Cultivating Climate Resilience in the Gardens of Trinity

Under the leadership of Head Gardener Karen Wells, Trinity’s Garden Department has taken ambitious steps to adapt planting strategies, reduce water use, shift away from fossil fuels, and foster biodiversity. The team’s mission is clear ‒ to cultivate a tranquil and inclusive environment that supports wellbeing, reflects sustainable values, and models ecological responsibility – and is underpinned by a Climate Resilient Garden Strategy. One of the most celebrated recent initiatives is the creation of a woodland walk in a previously wild part of the grounds. Built entirely from reused materials sourced from the gardens themselves, the new path offers “an amazing space for everyone to enjoy and decompress,” says Karen.

Rainwater harvesting has already been piloted through a 23,000-litre tank, while an orchard at Burrell’s Field is irrigated with rainwater captured from nearby roofs. Future plans include expanding collection to additional buildings across the estate.

The team has also launched or supported a suite of citizen science and biodiversity initiatives: from the Big Bird and Butterfly Counts, to use of the iRecord and eBird platforms, to regular surveys with leading academic partners including Dr Chris Preston, Andrew Dobson and Dr Jonathan Shanklin who help record birds and wildflowers. These efforts are creating a rich picture of species diversity across the College grounds and informing targeted interventions. New planting approaches reflect this data. The College has trialled drought-tolerant borders, low-maintenance perennial gardens, and a “no-dig” cutting garden to reduce soil disturbance. Weeds, once a target for chemical control, are increasingly reclassified as ecological assets. Sustainable pest management is now preferred over routine pesticide use, and alternatives like hot water weed machines and electric brushes have been trialled, with other colleges invited to observe and share learnings. Over 1,000 specimen of trees are managed through Trinity’s MyTrees database. As climate pressures intensify, the Garden Department is introducing more resilient species and increasing tree ring mulching to reduce water stress. Replacement planting is informed by guidance from Kew Gardens and the Tree Design Action Group (TDAG).

Work in the gardens is not only technical, but also deeply human. Staff well-being has become a design consideration in its own right. For example, shade, UV protection, and heated gear are now standard tools in a gardener’s kit. New welfare facilities and charging infrastructure are planned to support the battery-powered future of the department.

Students, staff and Fellows can pick up posies or fruit picked from the Trinity Gardens for a Great Court pop-up stall. Photo: Graham CopeKoga.

Students, staff and Fellows can pick up posies or fruit picked from the Trinity Gardens for a Great Court pop-up stall. Photo: Graham CopeKoga.

Engagement is central. Guided tours, open days, and Freshers’ Week presentations have helped embed awareness across the College. Wildlife cameras and pop-up events, like “Foliage Friday” and a pop-up flower stall, bring a fresh touch to serious ecological education. Meanwhile, connections with other college gardening teams have been revitalised, with Trinity hosting demonstrations and knowledge-sharing sessions with other colleges.

Investing for the Long Term

If Trinity’s buildings and land reflect the visible dimension of its sustainability agenda, then its endowment represents the invisible engine – an investment portfolio powering academic life, physical upkeep, and institutional resilience. For centuries, the College has maintained and grown this endowment with a singular purpose: to provide stable, long-term funding for its charitable mission. Today, that purpose is being renewed through the lens of sustainability.

The endowment, now valued at circa £2.5 billion, supports more than just Trinity’s internal needs. Its income underwrites contributions to other Cambridge Colleges, to departments across the University, and to external philanthropic efforts within the city and beyond. As such, the way it is invested and the values it represents matter not only to the College, but to a wider set of stakeholders. “The changing climate poses a great risk to our College and its wider communities, as well as our planet,” says Romane Thomas, Investment Manager at Trinity. “This is why we invest with the long-term sustainability of our College as a guiding principle, so that Trinity can continue to operate as a world leading academic institution for the next 500 years.”

The endowment’s aim is to achieve sustainable long-term returns, with a target of CPI +5% and a focus on sustainability including, since 2021, a commitment to lasting, positive environmental impact and achieving net zero by 2050. This approach aligns with fiduciary duty while recognising the systemic risks posed by climate change and the opportunities emerging from the transition to a low-carbon economy. The College is also taking a progressive stance on its landholdings, with more than 8,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent having been saved due to actions on the property portfolio since 2019.

One of the most visible examples of this alignment is the transformation of the Cambridge Science Park – a 150 acre commercial asset founded by Trinity in the 1970s and now home to over 7,000 employees across more than 100 firms. Since 2019, the College has committed to a major decarbonisation of the site, with 50% of Trinity’s buildings there now no longer using gas.

Students head to a TrinityPlus programme entrepreneurship session at The Bradfield Centre, based at the Cambridge Science Park.

Students head to a TrinityPlus programme entrepreneurship session at The Bradfield Centre, based at the Cambridge Science Park.

Other assets owned by the endowment and historically leased to tenant farmers are now being repositioned to support a regenerative model – one that considers biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and soil health as core forms of value. A pilot biodiversity assessment on the Brightlingsea Estate has mapped habitats, species richness, and ecological risks, creating a baseline for ongoing monitoring and improvement. Meanwhile plans are in place to expand the Trimley Nature Reserve from 85 hectares of habitat to 117 hectares.

Innovative approaches to land use are not confined to farming. Land acquired nearly a century ago near Newark for sand and gravel quarrying has, in partnership with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), been transformed into a thriving nature reserve that now attracts uncommon species such as the bittern, bearded tit, hobby, eel and otter.

There are, of course, trade-offs. Retrofitting in heritage or scientific environments means navigating planning restrictions and technical compromises. On agricultural estates, balancing productivity with biodiversity involves cultural as well as economic change. But Trinity’s leadership believes these tensions can be managed, and that by being transparent and collaborative, the College can act as a bridge between old systems and new imperatives.

In terms of financial assets, Trinity has diversified exposure to sectors and funds that contribute to sustainability. It holds positions in climate-oriented venture capital, including funds that support renewable energy infrastructure, circular economy technologies, and biodiversity measurement tools. In the public equities space, the endowment does not hold fossil fuels and managers are assessed not only for performance but for how effectively they integrate ESG (environmental, social, governance) metrics – and how transparent they are in reporting them. This leadership has been recognised at a national level, with Trinity receiving a Green Gown Award for its work with the banking sector on climate finance.

Research in Service of Change

Beyond the physical estate and the endowment, Trinity College’s influence on sustainability extends into a powerful global domain: research. As one of the most intellectually vibrant communities in Cambridge, Trinity is home to past and present scholars, researchers and alumni such as Jerome Neufeld, Sir David J. C. MacKay, Emily Shuckburgh, Lord (Martin) Rees, Hugh Hunt, Adam Boies and David Baulcombe, whose work is shaping how societies understand and respond to environmental and social challenges, from implementing policy at a national level, to educating the next generation of Trinity’s students on how they can find solutions to climate change.

In 2024–25, the College supported and celebrated a wide array of sustainability related research across disciplines. This included studies in biodiversity economics, AI applications for climate modelling, food systems behaviour, low-carbon design, and environmental law. The diversity of this work reflects Trinity’s distinctive character – a place where blue-sky thinking and applied science intersect, and where Fellows, students, and collaborators push boundaries together.

The College also provides a supportive environment for emerging voices in climate and environmental research. PhD students affiliated with Trinity are exploring topics including peatland restoration financing, climate risk disclosure frameworks, and ecological data ethics. In addition, Trinity’s Fellows are deeply engaged with public policy. Some serve on government advisory panels, contribute to global research collaborations, or consult with intergovernmental organisations. This includes involvement in the UN’s High-Level Expert Group on Net-Zero Commitments and advisory roles for DEFRA and the UK Infrastructure Bank. In each case, the work is rooted in rigorous analysis and animated by a commitment to public good.

Food for Thought

Trinity’s commitment to sustainability is also embedded in something more universal and everyday: the food served to its Fellows, students, staff, and guests. The College has eliminated single-use plastic containers, phased out plastic straws and bottles, and begun bottling 50% of its water in-house using reusable containers. Behind the scenes, kitchens have been retrofitted with high-efficiency electric systems, while used cooking oil is converted into biofuel, saving over 100 tonnes of CO₂ in one year alone.

Sourcing policies have also evolved. Today, meat served at Trinity comes from surrounding counties, our fish from British waters, while all eggs are free-range. Only seafood rated 1–3 by the Marine Conservation Society is used, and menus are seasonally aligned wherever possible. These are not just procurement decisions, they reflect a wider ethos of stewardship and accountability in the food chain.

Looking forward, the Catering Department is exploring the introduction of self-service dining as a way to reduce plate waste and give diners more control over portioning. Better data collection will support improvements in menu planning and resource allocation, while efforts to upgrade student food facilities will continue. It is a complex challenge, particularly in a community as diverse and tradition-rich as Trinity’s. Yet by combining leadership, collaboration, and curiosity, the College is turning its kitchens into active sites of climate action.

Importantly, this work is not led by a single sustainability officer, but by a collective leadership team under the guidance of Ian Reinhardt, Head of Catering. Under his leadership the team has not only reimagined how Trinity feeds its community, but also how it can influence the wider sector. Reinhardt was chair for five years and is now a Committee member of the Cambridge Colleges Procurement Management Group, which coordinates food purchasing across multiple colleges, increasing purchasing power, raising sustainability standards, and securing better value through collective intelligence. As Ian Reinhardt says: “Every meal is an opportunity to make a difference. By simply rethinking how we source ingredients, design menus, and reduce waste, we’re showing that sustainability can be practical and collaborative without compromising on quality.”

Trinity has also explored opportunities to foster academic research linked with catering. One prominent example is the research of Dr Emma Garnett, whose work on sustainable food consumption has gained international recognition. In partnership with catering staff and students at Trinity and other colleges, she ran real-world trials on meal presentation, menu labelling, and vegetarian defaults. The results, published in Nature Food, revealed how modest interventions, such as repositioning plant-based meals or changing defaults, could significantly increase uptake, helping to lower the carbon footprint of College dining without diminishing standards or student choice. Thanks to this research, Trinity’s kitchens have become early adopters of these so-called “sustainability nudges.” A growing culture of data-informed menu design is taking shape, with the College now exploring how to embed sustainable food procurement and behavioural science into its long-term strategy, not just in dining halls, but across all food service areas.

Such initiatives illustrate a core strength of Trinity’s academic culture: its ability to act as a testbed for wider systems innovation. When a research idea is trialled in the College kitchen or in a lecture hall’s lighting system, it isn’t just a local experiment – it’s a prototype with global implications.

Looking Forward One Year and Five Years On

In the coming year, the College will move forward with the implementation phase of its heat decarbonisation strategy. Following extensive technical and feasibility work, building services teams will begin delivering on planned retrofits for Burrell’s Field and Pearce Hostel. These pilot sites will serve as a learning platform for future interventions, with a view to expanding heat decarbonisation to additional buildings across the central College footprint. Alongside this, energy use across all estate areas will be reviewed with a focus on demand reduction and behavioural change.

In Trinity’s gardens, the team plans to catalogue the health and climate resilience of the entire plant collection, drawing on advice from experts including Kew Gardens and Cambridge University Botanic Garden. Experimental drought tolerant beds, such as gravel and sand borders, will complement a feasibility study into expanded rainwater harvesting.

Habitat creation will continue, including new features like hibernacula and wild areas, supported by lower mowing regimes and understorey planting. A phased transition away from box topiary and the replacement of dying trees with climate-resilient species will reshape planting across the estate.

A wild area underneath the magnificent chestnut tree in New Court.

A wild area underneath the magnificent chestnut tree in New Court.

Operational sustainability is also front of mind. The team will keep phasing out fossil-fuel equipment, improve welfare facilities and electric charging points, and trial further chemical alternatives.

On the investment side, work on rural landholdings will also continue. The biodiversity pilot on the Brightlingsea Estate will enter its second year of assessment, with insights feeding directly into tenant engagement and regenerative land management planning.

Trinity’s asset managers and external advisors are refining models for climate risk exposure and scenario analysis. The College will continue to build its capacity in active ownership, including exercising shareholder voting rights, engaging portfolio companies on climate strategies, and encouraging transparency in ESG reporting.

Research, too, will remain central. Trinity intends to deepen its support for doctoral and postdoctoral researchers focused on sustainability-related questions. The College is also exploring thematic funding opportunities, including convening seminars and cross-disciplinary projects that connect environmental research with technology, governance, and ethics.

At the five-year horizon, the ambitions are bolder still. Trinity aims to be a recognised institutional leader in the transition to a low-carbon college. This means not only meeting net-zero goals operationally, but demonstrating best practice in investment stewardship, land management, research enablement, and public communication.

A renewed Trinity

Trinity College’s sustainability journey will continue to be woven through every aspect of College life. This is not a siloed initiative, confined to a green team or a policy document. It is becoming part of the College’s operational DNA – embedded in how decisions are made, how investments are evaluated, how buildings are maintained, and how research is pursued.

The task ahead is large. But Trinity’s legacy of stewardship, inquiry, and courage suggests it is equal to the challenge. In placing sustainability at the heart of our mission and priorities, the College is staying true to its past, while protecting and shaping its future, all in service of advancing “education, learning, religion, and research… in perpetuity.”

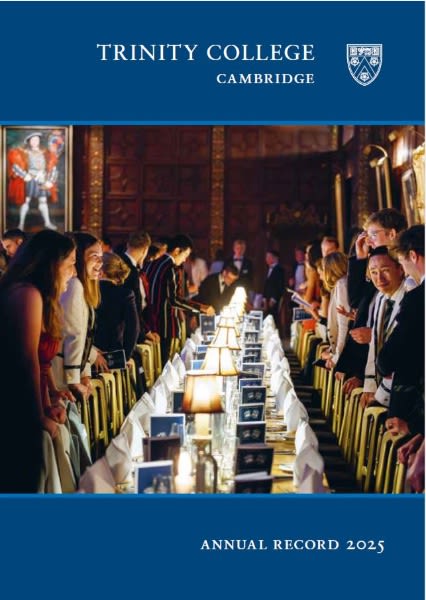

This article is included in the latest edition of the Annual Record.